The fault lines over Canada’s carbon emissions

Posted by Daniel Hoornweg on July 11, 2019

Social seismologists – those people who study social tectonics and growing tensions between communities – are worried about Canada. Strains over carbon emissions and the future of the oil and gas sector are severe as Alberta and Saskatchewan grow apart from the rest of Canada.

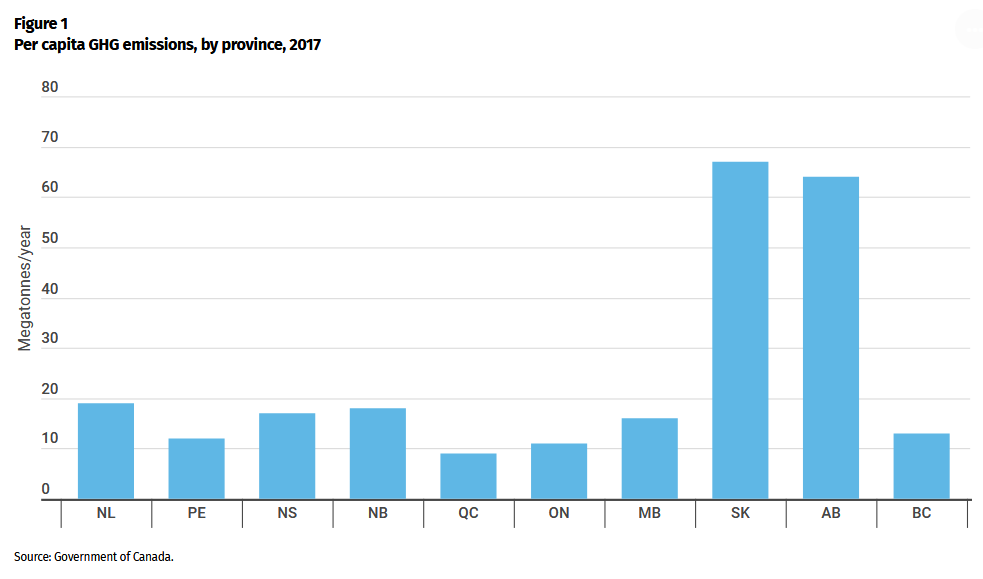

The emissions are enormous and the rising pressure is already stressing the Canadian federation. Figure 1 highlights the challenge. Alberta and Saskatchewan’s carbon emissions are over 60 tonnes per person annually, and growing. These emission levels are the highest in the world, by far – if Alberta and Saskatchewan were independent countries their carbon emissions per person would be more than twelve times the global average. By contrast, provinces like British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario are between 10 and 20 tonnes per person per year, and all declining.

Tension between countries is increasing over carbon emissions and climate change. The Paris Agreement signed by 196 countries in 2015 (including Canada) committed to keep global warming below a 2°C increase from pre-industrial levels (with an aspirational goal below 1.5°C). With impacts of climate change already being experienced by many countries, especially those closer to the equator, and with global carbon emissions still steadily rising, most countries are naturally nervous.

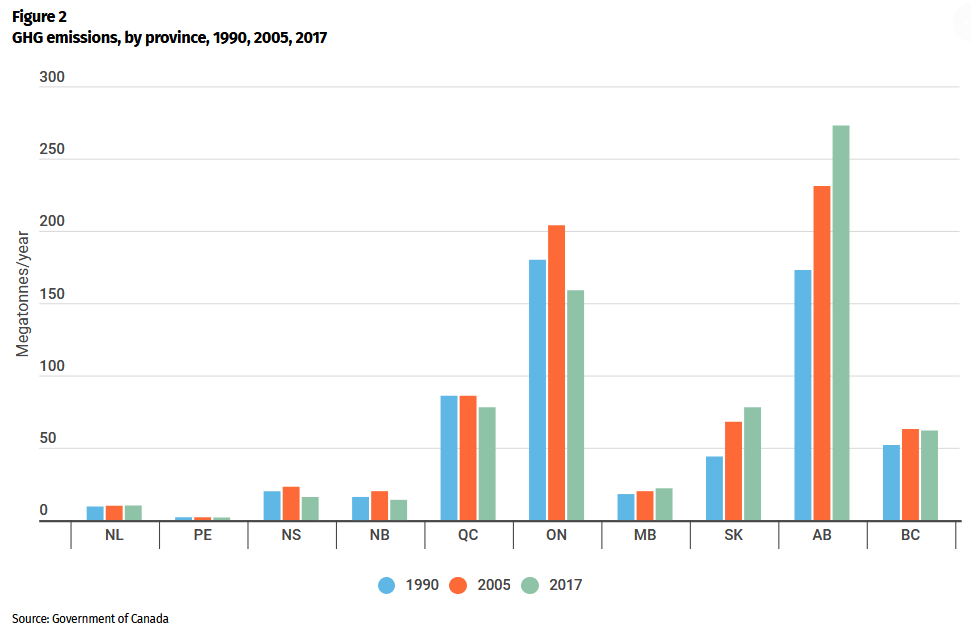

Canada committed to reduce GHG emissions by 30% below the 2005 level of 732 megatonnes of CO2 by 2030 (and a long-term agreement of 80% below the 2005 level by 2050). To put these values in perspective, each Canadian on average was responsible for 22.7 tonnes CO2 in 2005 (see Figure 2). We have committed to reduce this to 12.5 tonnes per person in 2030 and just 3.3 tonnes per person in 2050[1].

When carbon emissions are presented per person, Canada’s failure to act is striking. Canadians surpassed the U.S. in emissions per capita last year, and now are poised to be the highest per person carbon emitters in the world (only Saudi Arabia and Australia are higher but Canada is on track to overtake them within a few years).

Canada’s options are limited. The country could signal its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement like the U.S. did, and like Canada did in 2011 with the Kyoto Protocol when Canada failed to meet its target of 6% reduction of 1990 levels. Canada was the only country to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol. However, failure to remain within global partnerships also has high costs. The cities of Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver and Ottawa and to a lesser extent Calgary-Edmonton would be impacted the most, as their economies shift to emerging global technologies like artificial intelligence and ‘smart services’. As a ‘middle global power’ Canada cannot afford to go it alone. Despite what path the U.S. takes, Canada’s future wealth is largely bound to emerging urban centres around the world, all of which are struggling to reduce carbon emissions while meeting growing energy demands.

Canadians will be under intense international pressure to reduce emissions as climate impacts intensify, particularly in countries that contributed little to the problem but are impacted severely, such as Bangladesh, Thailand, Indonesia and those in Africa.

Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia will be increasingly reluctant to offset Alberta and Saskatchewan’s growing carbon emissions. A third of Canada’s carbon emissions are from the oil and gas sector; this is the only sector expected to grow over the next 20 years. This is further complicated with the predicted global drop in the price of oil. All Canadians will be asked to pay a higher price for declining fossil fuel revenues.

These challenges are behind the tension about new pipelines and a price on carbon. The challenge may be beyond the capacity of our current political systems. So far the problem of Canada’s growing carbon emissions has been addressed through shifting allegiances and factions. Regardless of political affiliations, this challenge cannot be overcome through partisan pressures. Canada needs an economic roadmap away from carbon and all Canadians need to travel this path together.

These tensions are not new. From its inception Canada has worked to prevent communities from drifting apart by building railroads, highways, communications and postal systems.

Climate change is considered a ‘force-multiplier’; it can make bad things much worse. The tension over carbon emissions could break Canada apart. Conversely, Canada could emerge as one of the first larger-scale countries to successfully wrestle with the trade-offs of a shift away from fossil fuels. Climate change could be the catalyst that brings together Canada’s disparate factions, along with other parts of the world. Canadians will be choosing soon – the pressure’s on.

[1] For reference, flying from Canada to Europe or the Caribbean generates about 2 tonnes CO2; heating an average Canadian home with natural gas is about 4.5 tonnes per year, and the average car generates about 5 tonnes per year. Planting one tree should reduce carbon emissions by 1 tonne over the life of the tree (if no forest fires).

Filed under: Sustainability 101